South Africa is fighting to spread Covid vaccines

Initially worried about side effects, the South African street vendor Palesa Sekwere slowly comes up with the idea of getting a vaccine against the coronavirus.

“I am positive. . . the time will come to tell me to get this, ”said the 32-year-old in Soweto, Johannesburg’s largest township.

But the bigger problem for Sekwere is that she’d have to tear herself away from the food stall selling one-edge snacks like magwinya, which is a type of donut. Although their booth is directly across from a clinic where dozens of people sit on plastic chairs and wait for bumps, “I can’t” [easily join them]because I work here, ”she said.

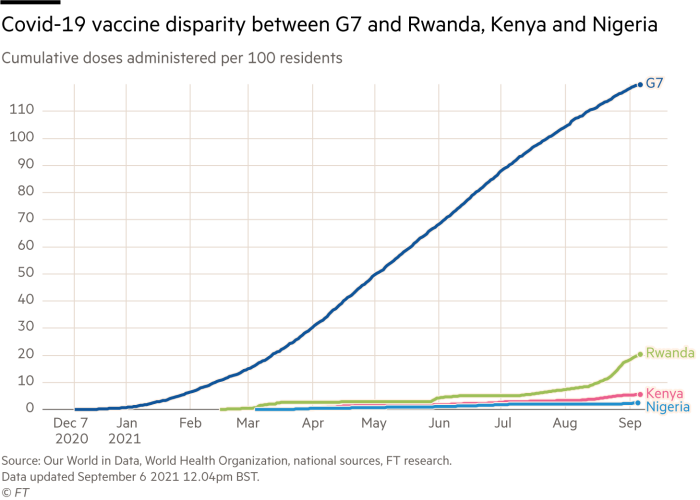

So far this year, South Africa has led the major African economies by accounting for 17.5 percent of its population, or 7 million, compared to less than 3 percent of total Africans in a continent that is at risk of falling further as richer countries make it hunt for limited global supplies.

Although his relative financial strength has enabled him to purchase vaccines in advance and in bulk, the admission falls short of the goals set by President Cyril Ramaphosa’s administration, mainly because of difficulties in distributing vaccines to the poor.

Jabs are open to anyone over the age of 18, and the public and private sectors administer 1 million doses about every four days, every 14 days in June. This is still below the daily capacity of around 300,000 to 400,000 cans, a sign that voter turnout is declining.

With more than 200,000 estimated deaths from Covid-19 due to excess mortality rates, South Africa is the African country hardest hit by the pandemic, and about three-quarters of South Africans want vaccines, according to recent polls.

But the poorest are also most likely to have problems traveling to vaccination centers, being taken off work or receiving information about vaccination plans. The rural areas of Eastern Cape and Limpopo, two regions that have hosted outreach programs to address these issues, have vaccinated the highest proportion of their adult populations of any province.

“We have an intake problem, but I think it has to do with distribution,” said Russell Rensburg, director of the South African Rural Health Advocacy Project.

“Those left behind”

As vaccine adoption slows down, some South African companies are starting to mandate vaccinations. In early September, Discovery, South Africa’s largest medical services provider, and Sanlam, Africa’s largest insurer, said they would require vaccinations for all employees from early next year – the country’s first major public companies to do so.

Recommended

South Africa’s government is not yet considering a national mandate, said South African Health Minister Joe Phaahla. “Our priority is to mobilize and convince people to volunteer.” Meanwhile, the South African Football Association is planning to offer vaccinated fans free tickets for an upcoming national game against Ethiopia.

In a country with an official unemployment rate of more than 34 percent and where many like Sekwere depend on informal work for a living, vaccination orders from employers can in any case have relatively little impact.

Concerns about the hesitation rates in richer countries are projected onto a country where logistics is a bigger obstacle, Rensburg said. “The US had previously achieved 50 percent vaccinations” [hesitancy] became a problem. We’re not even at 20 percent. “

South Africa should focus on “those who are left behind or those who have not been opened”, such as high-risk over 50-year-olds, said Rensburg. “We have the tools, we just don’t use them. . . If we can get these rural vaccinations right, we can hopefully provide a base for other African countries. ”

Desperate for supplies

Outside of South Africa, security of supply remains a priority on the continent. Rwanda’s President Paul Kagame said this month that compulsory vaccinations are a “far-fetched problem” for his country, where only around 900,000 of its 13 million residents are fully vaccinated. “How can you make vaccination compulsory if you don’t have vaccines?” he said.

Last week, Covax, the World Health Organization-sponsored program for delivering vaccines to developing countries, cut its forecast for deliveries this year by about 25 percent. After supply issues with AstraZeneca at the Serum Institute of India, the African Union (AU) has reached an agreement to source 400 million doses of J&J by then next year.

“We doubled J&J. Since it’s a single dose, it’s a very good product for us, ”said Strive Masiyiwa, AU’s special envoy for vaccine procurement. J&J deliveries remained sporadic, he said. Even South Africa received only about 12 percent of the 31 million doses the country bought, according to estimates by the South African Health Justice Initiative, an NGO that campaigns for Africa’s access to vaccines.

For now, ahead of a feared fourth wave, South Africa is trying to increase the take-up of the jab by emphasizing the availability of supplies. “Where we are now, even if all of Soweto shows up, we can vaccinate them. . . All we need are weapons, ”Health Minister Phaahla said last week during a vaccination tour in the community.

But while “it’s good to take the vaccine,” getting out of work and traversing the sprawling township isn’t easy, said Cebile Nqambule, 40, another street vendor in Soweto.

Comments are closed.